Overview Overview The fight against cancer has long focused on destroying tumor cells directly. However, the ecosystem in which a tumor lives—the tumor microenvironment (TME)—plays an equally critical role in disease progression and treatment resistance. A groundbreaking study led by researchers at the Institut Courtois d’innovation biomédicale (CI2B) and the Department of Pharmacology and Physiology at Université de Montréal has identified a new molecular target that not only stifles tumor growth but also reduces and reprograms the tumor’s blood vessels to invite a potent immune attack. The findings, published in Cell Reports, center on a protein called PAK2 and a chemokine known as CXCL10, offering a promising new avenue for enhancing immunotherapy.

The vascular problem in cancer In order to grow, solid tumors require that new blood vessels form within the TME, a process known as angiogenesis. However, unlike healthy blood vessels, tumor vessels are chaotic, leaky, and disorganized. This structural immaturity leads to poor blood flow and creates a hostile environment in which tumors thrive that often excludes the immune system’s “soldiers,” such as T cells, dendritic cells and Natural Killer (NK) cells, protecting the tumor from the body’s natural defenses.

Therapies aimed at destroying tumor blood vessels and normalizing them—by making them more structured and less leaky—to reduce tumor growth are available but shortcomings limit their efficacy. The research team, led by Dr. Jean-Philippe Gratton, investigated the role of p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2), a protein highly expressed in endothelial cells, the cells that line all blood vessels and initiate angiogenesis.

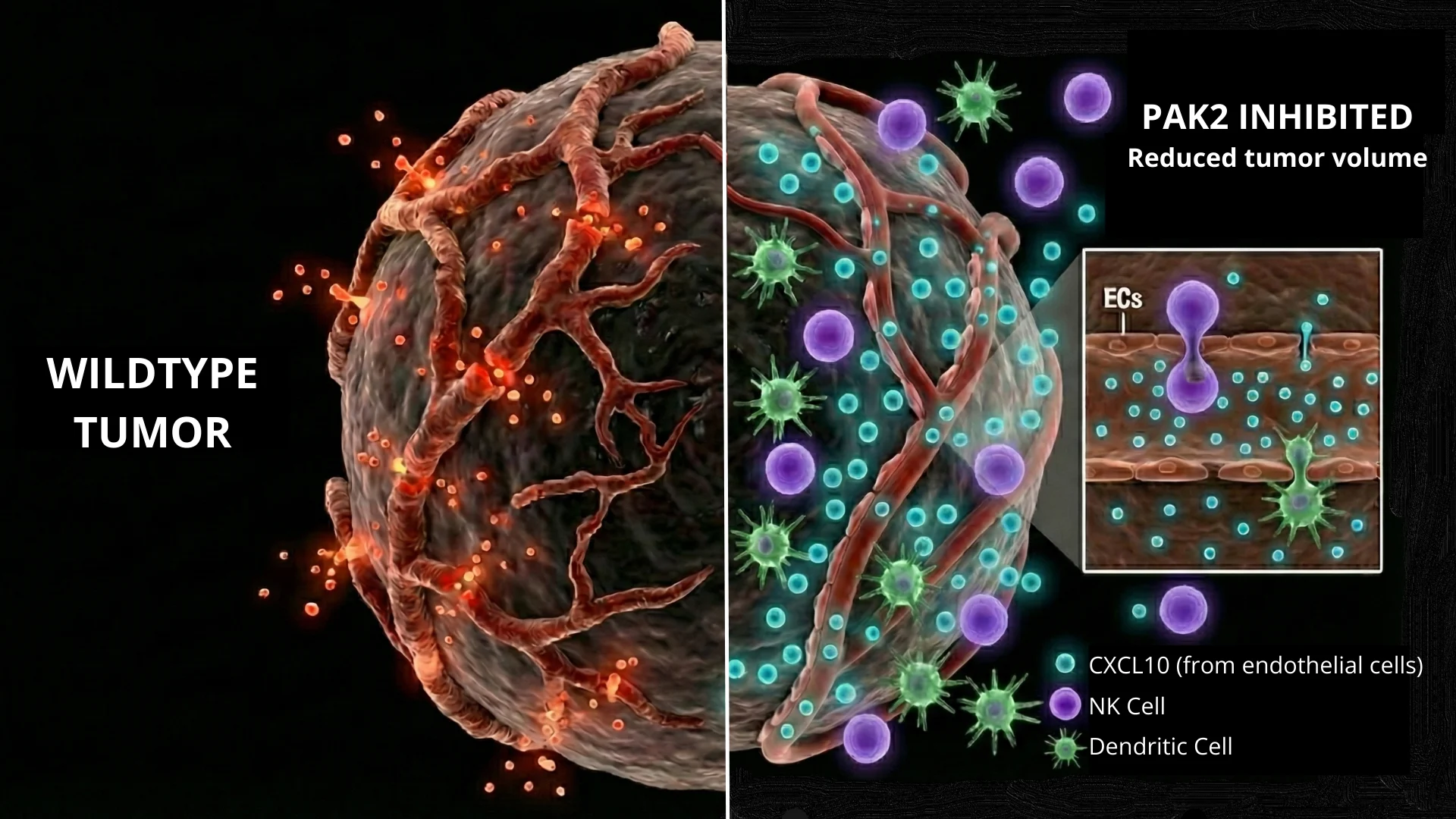

A dual mechanism: suppressing angiogenesis and enhancing immune response deleting the PAK2 gene specifically in endothelial cells of tumor-bearing mice, the researchers observed a marked reduction in tumor size and angiogenesis. Beyond simply reducing the number of vessels, the absence of PAK2 “normalized” the remaining vasculature. The blood vessels became more stable, with better coverage by pericytes (cells that support vessel walls) and significantly reduced leakiness. This vascular normalization is a critical step in turning a “cold,” immune-excluded tumor into a “hot” one that is susceptible to immune attack.

The most striking finding of the study was that the loss of PAK2 in endothelial cells triggered a robust innate immune response. The tumors deficient in endothelial PAK2 showed a significant increase in the infiltration of dendritic cells and NK cells, which are crucial for recognizing and killing cancer cells.

The immune connection: the CXCL10 axis To understand how deleting a kinase in blood vessel walls could summon immune cells, the team analyzed the genetic changes within the tumor. They discovered that PAK2 acts as a gatekeeper that suppresses the production of chemokines—signaling proteins that attract immune cells. Specifically, the deletion of PAK2 led to a surge in the expression of CXCL10, a potent chemoattractant.

The researchers demonstrated that CXCL10 is the key driver of these beneficial effects. When they blocked CXCL10 using neutralizing antibodies, the anti-tumor benefits of PAK2 deletion were reversed: the vessels became abundant and chaotic again, and the immune cells failed to infiltrate the tumor.

Implications for immunotherapy This study highlights endothelial PAK2 as a potential therapeutic target. By inhibiting this protein, it may be possible to reduce and reprogram the tumor vasculature to not only starve the tumor of resources but also actively recruit the immune system to the site of the disease.

“Our findings identify endothelial PAK2 as a potential target to limit tumor angiogenesis and reprogram endothelial cells to promote immune infiltration through CXCL10 signaling.” the authors conclude. This approach could be particularly valuable in enhancing the efficacy of existing immunotherapies, which often fail because immune cells cannot effectively penetrate the tumor core.

Collaborations This study was conducted in collaboration with researchers from the Montreal Clinical Research Institute (IRCM) and the Institute of Research in Immunology and Cancer (IRIC).